The Minimise Project wants to have better conversations about abortion. Given this, a big portion of our blogs focus on what we think are the best arguments for the pro-life position. But, of course, there’s more to having good conversations than that: it’s rare that you can have a ‘good conversation’ by just launching into a five minute speech explaining why everyone should agree with you. We want to think of ways to put our best feet forward when the topic of abortion comes up, or when we find ourselves bringing it up ourselves. If we want to have good conversations about such a controversial and sensitive issue, we need to have ways of dealing with disagreements, of effectively communicating ideas that might seem counterintuitive or even offensive, of listening to our interlocutors better, of training ourselves to be prepared to learn from them in the same way that we’d like them to be open to what we have to say. Of course, all this is easier listed out than done in the real world. So, sometimes we also write about barriers that we have to overcome in order to have these conversations – including common psychological tendencies that we would probably all do well to be mindful of so as to be on guard against them (though, to be clear, none of us have any expertise in psychology!).

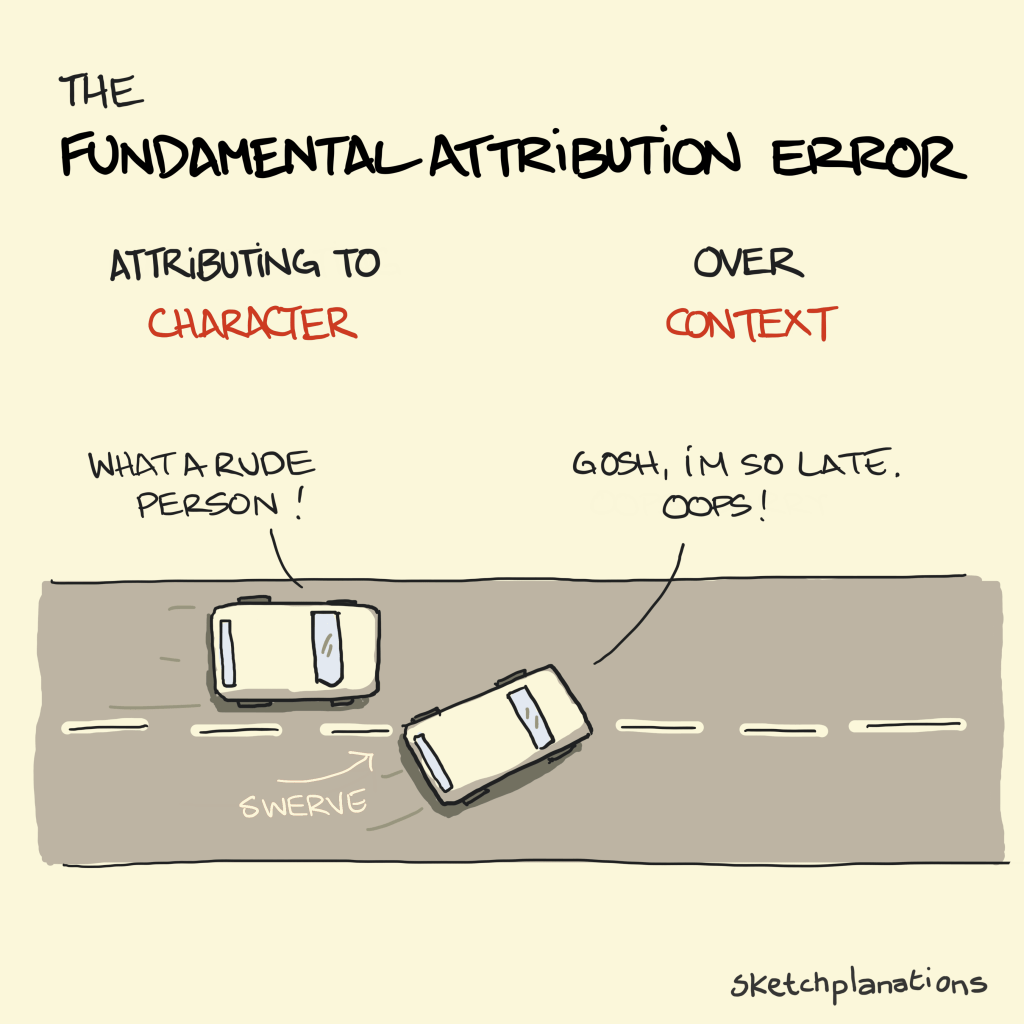

One such common tendency is sometimes called the fundamental attribution error. The phrase was coined by social psychologist Lee Ross in a popular paper that he wrote in 1977. For our purposes, the fundamental attribution error is a mistake that we are all naturally inclined to make because of how our minds work. We have a tendency to underestimate the role that situational and environmental factors play in explaining other people’s behaviour (e.g. ‘She didn’t get much sleep and is exhausted’) while overestimating the role of character traits or other personality factors (e.g. ‘She’s rude and thoughtless’). In other words, we tend to automatically assume that other people’s personality traits have more of an influence on their behaviour relative to other factors outside of their control than they actually do. Meanwhile, we’re happy to explain our own behaviour – especially our own less than ideal behaviour – by appealing to situational factors beyond our control (e.g. ‘I was rude, but this is not because I’m a rude person. It’s because I’m exhausted’).

The upshot of this is that when we see other people behaving in ways we disapprove of, we are more likely to think that they are behaving this way because ‘that’s just the way they are’. When we notice that we ourselves are behaving in ways we do not approve of, we are more likely to think that this is because of circumstances outside our control. When a colleague is late for work for a month, our first instinct might be to think that they are lazy or disorganised. If we ourselves are late for a month, we are more likely to think that the reason for this is our circumstances – maybe we’re going through a rough time- rather than our personality. (To be more precise, we overestimate the extent to which ‘the way they are’ explains other people’s behaviour and we underestimate the extent to which their circumstances do. Maybe we think that our colleague’s lateness is partially excused by some unknown circumstances but also somewhat explicable in terms of their character. But we still give the latter too much weight in comparison to the former. But that’s more of a mouthful!)

One consequence of this is that we might have a natural tendency to let ourselves off the hook when we might do well to cast a more critical eye on our own character, but then also have a tendency to hold other people 100% accountable for their actions and give inadequate weight to the possibility that they might have just as many excuses as we do. Perhaps this is not an especially novel idea: the warning against judging others in a way that we don’t want to be judged ourselves is a very old one; as is the suspicion that we might have a tendency to do so anyway, fixating on motes in other people’s eyes while ignoring beams in our own.

Now, why might this be relevant to conversations about abortion? Easy! People engaging in these debates, on all sides, routinely behave in ways that are less than ideal when engaging with one another – whether casually in person, online, or through the workings of more official organisations and spokespeople. And so, given what we know about the fundamental attribution error, there’s good reason to worry that we might be likely to judge other people more harshly than they deserve for this behaviour, while excusing ourselves. This isn’t conducive to mutual understanding and good conversations!

What can we do about this?

A potential first step is to try to think about how things look from other people’s perspectives, or to imagine ‘living life in their shoes’. A second is to take more seriously the possibility that our behaviour and that of other people could be negatively influenced by the wrong circumstances and our environment and to try to mitigate this. I’ll look at both of these strategies in more detail in my next blogs.

In the meantime, where might we encounter this ‘fundamental attribution error’ bias? It seems to me like it is likely to crop up when, for example,

- We encounter pro-choice people who we feel are hostile or judge us harshly. It might be easy to assume that they are judgemental or hostile people rather than considering the possibility that there might be any number of explanations for this behaviour and that they might be perfectly lovely people . They might be having a bad day, be upset by something you said for personal reasons…. or they might have even fallen prey to the fundamental attribution error themselves!

- We accuse other groups of being unusually biassed or irrational. Maybe things just look different from where they’re standing.

- There is probably something similar to be said about fraught interactions between pro-life groups who adopt different tactics to each other.

So how can we deal with conversations or contexts that bring out the worst – or at least the ‘less than best’ – in us or other people? While we can start by avoiding them, there are other strategies we can use: tactics to transform these contexts while we’re in them, to make them less likely to exist in the first place, and to try to understand and empathise with people who these contexts might encourage us to think of as ‘opponents’ or ‘enemies’.

To be continued!

Ciara