One thing I often hear from pro-life people is how completely silenced they feel in the public arena. It seems that everyone in mainstream society believes abortion access is an unambiguously good thing, and anyone with an opposing view is not just wrong, they’re at best weird and at worst malicious. So many pro-life people feel that their point of view is simply not welcome in the vast majority of the spaces they live and move in, and that they cannot express their sincere and deeply held beliefs as a consequence.

I totally understand this feeling because I share it. It really does feel sometimes as though my view on abortion is akin to believing that women shouldn’t vote, or something equally ridiculous and outdated. In other words, the pro-life view feels like a view that simply cannot be expressed in polite company, and furthermore, it feels as though everyone agrees that I agree with them.

I’ve often wondered what to do about this. It seems the only answer is to get more people to speak up more about being pro-life, but this is almost like a chicken-and-egg problem – very few pro-life people speak up because very few pro-life people speak up. However, I recently came across a YouTube video that made some very interesting points about polarisation, and made me think perhaps pro-life people can be a bit braver, when presented with the right facts.

The video is only a little over ten minutes, and it’s well-worth watching the full thing. The video considers the role of social media in causing polarisation, which is increasing across the Western world. Until recently, it was presumed that social media meant you were primarily exposed to views that aligned with your own, with views you disagreed with being filtered out by the algorithm. Thus, people were sorted into ideological online bubbles, and therefore became polarised. Interestingly, this does not seem to be the case. In fact, people are exposed to a wider range of views online than they are in real life. However, the video claims that the internet, and social media in particular, is still to blame for increased polarisation – just not in the way we think:

Whether you want it to or not, your brain sorts people by worldviews and opinions into teams. This is not simply tribalism; it goes further. Researchers have called this process ‘social sorting’. On the digital town square, you encounter people that express opinions or share information that clash with your worldview, but unlike your neighbour, they don’t root for your local sports club. You’re missing the local social glue your brain needs to align with them. To your brain, the disagreement between yourself and them becomes a central part of their identity

In other words, the reason social media is responsible for polarisation is not because social media is bombarding us with opinions that all neatly align with our own. It’s because social media is bombarding us with people who are, as far as we can tell, nothing but an opinion. We don’t know these other people as people. We don’t know their favourite food, their opinion of Taylor Swift, their hometown, their job or profession. We don’t know anything about them other than the fact that they hold an opinion. If we like the opinion, we like the person, despite knowing nothing else about them. If we don’t like the opinion, we don’t like the person. We can’t really blame pro-choice people if they feel this way about us.

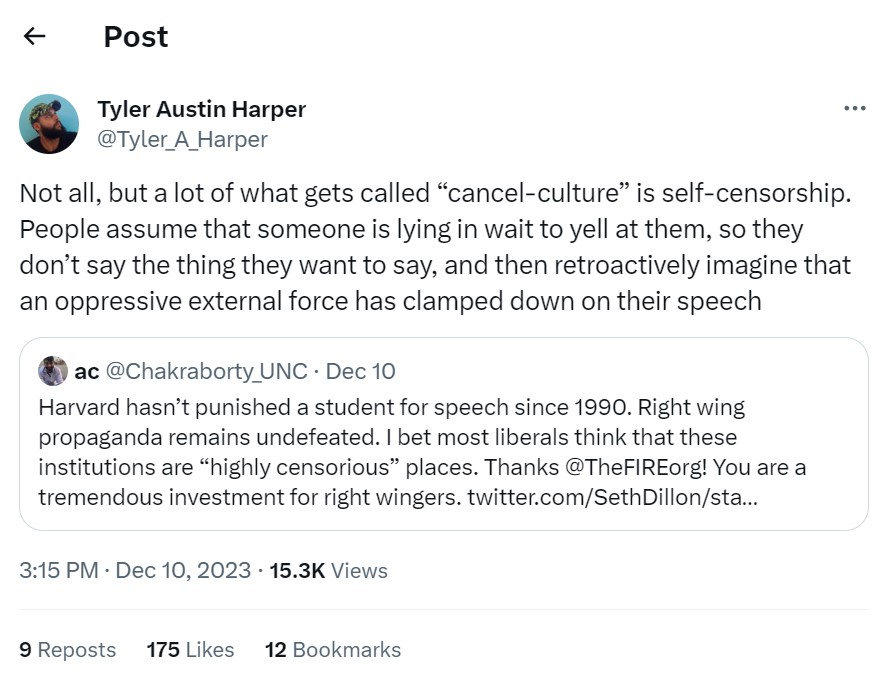

If all this is true, it doesn’t in any way change the fact that it can be very difficult to reveal that you’re pro-life – but it might make it a bit easier for two reasons. The first reason is that if we reveal our pro-life opinions to friends and family, we can rest assured that to these people, we are not just an opinion – we are a person. They know us, they like us and they trust us. Your friends and family are not going to react to your pro-life opinions the way they would react to opinions expressed by a stranger on social media, or in a Letter to the Editor, where they have no personal ties with the person in question. They may even be open or curious, rather than hostile, towards your opinion. The “cancel culture” that we all fear, based on the most hostile engagements we’ve witnessed online, may actually largely exist in our heads:

The second reason is that if pro-life people in general can be a bit more open, then all the pro-choice people we know will begin to associate the pro-life position not just with strangers in the media or online, but with actual people they know, and respect, and love. This means that, while they may not change their own position on abortion straight away, they will be more open to having pro-life opinions articulated. The pro-life position won’t seem as bizarre or as scary to them, because it’s not merely held by internet-inhabiting monsters who have nothing to recommend them.

All this means that having personal conversations with friends and family takes on a new urgency. We have to do this if we ever want the pro-life position to become mainstream, and as long as the pro-life position is not mainstream, we will make no progress.

If you’re wondering how to even begin having these conversations, we have some ideas to get you started. Ben has blogged about the three different kinds of conversation you can have about abortion: a great way to kick off is “I’m pro-life and I’m not a monster”. If you find even this is too scary, try reading about what to do if you’re pro-life and afraid. And if you’re looking for an even lower barrier to entry, you could take the advice of our friends over at Secular Pro-Life and memorise the following line: “I don’t want to argue about this, but for the record, I disagree.”One final note: being more open about your position on abortion is one of those things that gets steadily easier over time. The more you do it, the more you see that the actual conversation is rarely as scary as how you imagined it would be – and it’s never, ever as scary as debates online or in the media. Give it a try in a very low-stakes environment sometime. You may be surprised at the results.

Muireann